In the first of these Scrivener tips and tutorials series, I basically covered “What is Scrivener?, and hopefully you have a better idea about what Scrivener is and how it may help with your writing. I also suggested two Scrivener Bootcamp videos to help you really dive into Scrivener with great tips and techniques by a professional journalist and bestselling author.

In the first of these Scrivener tips and tutorials series, I basically covered “What is Scrivener?, and hopefully you have a better idea about what Scrivener is and how it may help with your writing. I also suggested two Scrivener Bootcamp videos to help you really dive into Scrivener with great tips and techniques by a professional journalist and bestselling author.

In this Scrivener tip, I want you to think of Scrivener as a giant binder. In that binder, you have dividers and tons of paper and photographs you need to organize.

Yes, we are going to start with visualizations. This will help you learn how Scrivener works and how to change your writing style and habits in and around it, and help you learn new words associated with Scrivener.

Imagine all the research you’ve done on your poems, stories, novel, and manuscript. You may have photographs to inspire your thoughts to a place, time, or person. You may have maps pinpointing locations and paths traveled. If you are really diving deeply into a novel or memoir, you probably have research files, digital and paper, the results of days, months, maybe years of studying the topic, place, and people you are writing about. You may have plot outlines, character sketches, and tons of notes.

How do you currently store all this information?

The digital files are most likely stored in folders, either in a collective dump or sorted by topic, place, and possibly date. To access them, you open your file management program and track them down, or open the program you use to view and work with them and hunt for them from there. This typically is Microsoft Word, PhotoShop, or variations on those popular word processing and photo editing programs.

Web pages are typically bookmarked, only accessible when you are online and connected to the web. You might have organized these by folders and subfolders, but it is also likely that you just marked them all as bookmarks in your web browser, the giant dumping ground for web pages you wish to return to in the future.

Tangible materials like papers, print-outs from the web, photographs, magazine and newspaper clippings, paintings, notes, napkins with notes…all these things are either in piles or sorted into folders in a filing cabinet.

Let’s see, you are multiple programs for accessing digital materials. You have reams of paper stuffed into files and folders, and that big metal filing cabinet collecting dust in the corner of your office a few steps from your computer desk. (more…)

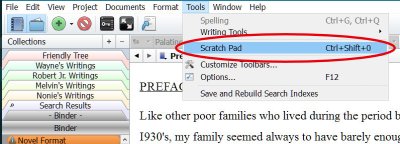

Ever get a new idea, a bit of inspiration, as you are writing? I used to turn to a piece of paper or sticky note to jot down my idea, but found that by the time I made the note and switched back to my writing program, I’ve lost track of what I’m writing. Moving my eyes from the computer screen and fingers from the keyboard invites distraction. Luckily, Scrivener offers a way to make notes and keep on writing.

Ever get a new idea, a bit of inspiration, as you are writing? I used to turn to a piece of paper or sticky note to jot down my idea, but found that by the time I made the note and switched back to my writing program, I’ve lost track of what I’m writing. Moving my eyes from the computer screen and fingers from the keyboard invites distraction. Luckily, Scrivener offers a way to make notes and keep on writing.