The “right” clause depends on many factors – there is no “one size fits all” – so be vigilant and pay attention, and make the right business decision for you and your book.

Today’s big take-away lesson is this: pay attention to the grant of rights, and know what rights you’re agreeing to give your publisher. A proper grant of rights lays the foundation for a positive, long-term business relationship between the author and the publisher – and that, of course, is good for everyone.

Do You Know Your (Publishing) Rights? – Susan Spann of Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers

Many of our Writers in the Grove members publish and share their work on our website here, often a first step toward publishing elsewhere such as on other websites, magazines, newspapers, and books.

According to many authors and publishing experts, one of the first things a professional writer needs to learn is what their publishing rights are, though it is often the last thing learned, usually after much confusion and frustration.

Writing is an art form, and professional writing is a business. There are business standards and practices. There are contracts, agreements, guidelines, and policies. You need to be professional in your writing and writing submissions.

Among all the things you need to learn before sending your work out into the world, you need to begin with understanding your publishing rights, the rights that determine who owns your work, how, where, and when it may be published, and how these rights influence your income from your written words.

Copyright and Trademark

To begin, let’s address the first two rights for writers, two that come with some confusion: the difference between copyright and trademark. When someone abuses your copyright or trademark, it is legally called a violation of your intellectual property. Both are intellectual property rights you will deal with constantly in your professional writing career.

Trademark protects brands and brand names. As a writer, you could choose to register your brand and author name, or the title of a book series, not the book title itself, as a trademark, protecting it from abuse and misuse, but that is a discussion for your legal professionals as you step through your career.

J.K. Rowling has long history of legal battles to protect Harry Potter and its entertainment empire. Some of those legal actions were over the trademark name of “Harry Potter,” “muggles,” and “Hogwarts,” including use of the name in fansite website addresses. Apple, Coca Cola, and many businesses protect their trademark name and brand by preventing trademark violations such as these. You are not allowed to use those names in your domain name or within your creative work unless it complies with their trademark rules and guidelines, or you receive legal permission, commonly called a license. (more…)

The Tom Paxton song made famous by Peter, Paul, and Mary, as well as John Denver, describes a thing that defines description, a child’s toy that was amusing all the same.

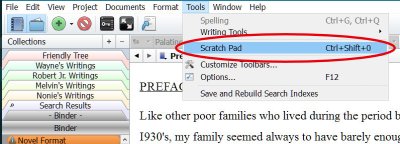

The Tom Paxton song made famous by Peter, Paul, and Mary, as well as John Denver, describes a thing that defines description, a child’s toy that was amusing all the same.  Ever get a new idea, a bit of inspiration, as you are writing? I used to turn to a piece of paper or sticky note to jot down my idea, but found that by the time I made the note and switched back to my writing program, I’ve lost track of what I’m writing. Moving my eyes from the computer screen and fingers from the keyboard invites distraction. Luckily, Scrivener offers a way to make notes and keep on writing.

Ever get a new idea, a bit of inspiration, as you are writing? I used to turn to a piece of paper or sticky note to jot down my idea, but found that by the time I made the note and switched back to my writing program, I’ve lost track of what I’m writing. Moving my eyes from the computer screen and fingers from the keyboard invites distraction. Luckily, Scrivener offers a way to make notes and keep on writing.

Your characters head for the local museum or art gallery. Their eyes are filled with wondrous sights. Colors, patterns, shapes, textures, renewing their spirit, giving them the beauty they crave in their life. Or boring them to tears as they’ve just been dragged to another thing-they-don’t-wish-they-had-to-do-in-order-to-save-a-realtionship-or-get-sex.

Your characters head for the local museum or art gallery. Their eyes are filled with wondrous sights. Colors, patterns, shapes, textures, renewing their spirit, giving them the beauty they crave in their life. Or boring them to tears as they’ve just been dragged to another thing-they-don’t-wish-they-had-to-do-in-order-to-save-a-realtionship-or-get-sex.  Artwork is encountered in most books in some way, a photograph of a suspect, a painting on a wall, a quilt, lacework, or arts and crafts item that tells us more about the character, place, or solves a mystery. How do you describe it to not only let the reader see see it, but also choose words that match the tone, scene, time, and owner?

Artwork is encountered in most books in some way, a photograph of a suspect, a painting on a wall, a quilt, lacework, or arts and crafts item that tells us more about the character, place, or solves a mystery. How do you describe it to not only let the reader see see it, but also choose words that match the tone, scene, time, and owner?